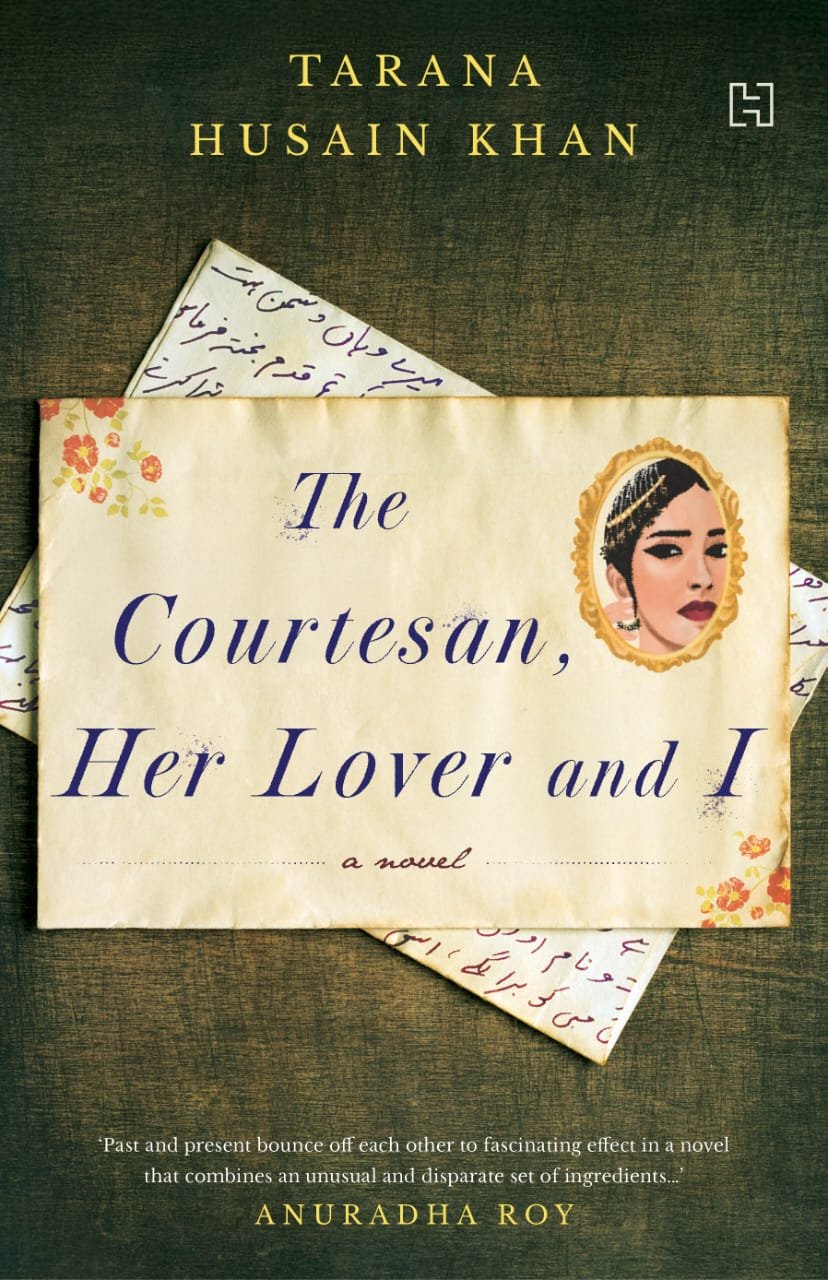

Other stories come like the whispers of the past, bringing with them parts of memory, desire, and forgotten voices. The Courtesan, Her Lover, and I by Tarana Husain Khan is such a piece, a novel that traverses centuries and brings together the lives of Munni Bai Hijab, a courtesan-poet in nineteenth-century Rampur, and Rukmini, a modern-day writer who stumbles upon the letters of Daggh Dehlvi in the archives.

Beginning as a literary discovery, it then evolves into a reflection on love, erasure, and the boldness of women who demand to write themselves into history.

The core of the story is Hijab, a woman whose company was so enchanting to the renowned Urdu poet Daggh Dehlvi. His letters to her, which are full of chide and desire, show his passion and his insecurity.

In a single letter (undated), he mourns that she was absent after two days at Nawab Haider, enquires whether she was faithful, and begs that she should pay attention to him.

The language is crude, nearly frantic, and the language lays bare the frailty of a man whose reputation had been made on wit and verse but whose heart had been shattered by the decisions of a courtesan.

Daggh had made Hijab immortal through poetry, but in so doing, he silenced her voice more than her own, a conflict the novel attempts to amend.

Even Hijab herself becomes a bright representative. The descriptions of her looks, her aquiline nose, her huge black eyes, her laugh that fills rooms, her affections for paan and burqa make her both sexy and human.

Not a far-away icon but a woman of the flesh and soul, she must find her way through the twists and turns of love, allegiance, and survival in a principled kingdom where courtesans were both glorified and policed.

Her presence changed the times of the courtly life of Rampur; friends of Daggh were jealous of the time he spent with her, and the pride of Nawab Hasan was humiliated by her magnetism. However, Hijab was always at the center, a character that destabilized order and aroused a cult following.

The novel is not tied down to the past. Over a hundred years later, Rukmini, a Hindu woman in a Muslim family, comes across the letters written by Daggh at the Rampur Raza Library. Her interest in the Hijab is seen as a reflection of her life.

The world of Rukmini is one of silent dissatisfaction: a husband pursuing failed enterprises, a daughter who leaves medical school, and a friendship with Daniyal, the stern protector of the Rampur legacy, which turns out to be a romance.

The fear of becoming like her mother, the woman who had abandoned their family, haunts her even as she is drawn to the story of Hijab, the power and desire.

This two-story format enables the book to discuss kinship over time. Hijab and Rukmini live centuries apart, yet they both endure oppression through erasure.

Hijab was drowned in the glory of Daggh; Rukmini’s identity is in danger of being overshadowed by family values and social conventions. Both women want to prove they are their own writers, their own narratives, not to be narrated by others.

The atmosphere has been overlaid in prose. Courtyards wet with rain, kite-fighting, music, and poetry nights all bring back the richness of Rampur’s cultural world. Being a musical fanatic, as compared to the albeit smaller scale of Nawab Wajid Ali Shah, puts Daggh in a context of patronage and decadence.

But it is Hijab who brings these scenes to life, her seizing life and her humour charming those nearby as she drops out of Hyderabad, music dies, which highlights her position as an inspiration and a distractor.

The novel does not diminish the Hijab to a one-dimensional aspect, and this is what is quite captivating. She is seductive, but helpless, renowned but discarded, resilient, but hurt.

Her contradictions reflect the ambiguity of female lives in the patriarchal world, where fame is short-lived, and memory is selective. The story demands her humanity and presents her not as a courtesan, but as a woman of ambition, tact, and persistence.

The sections of Rukmini, in their turn, base the story on the realities of the present day. Her family predicaments, her false fumbling with desire, and the effort to create a writer’s voice can be heard by the reader who is just familiar with the burden of expectations and the terrors of being the shadow of another person.

Her trip is not merely about discovering the history of the Hijab, but about how she navigates her current life.

The novel raises more questions about history and memory. Why do we still remember some people’s lives and forget others? What role do gender, politics, and convenience play in shaping collective memory? The story of Hijab is a brilliant example of how inconvenient lives, or lives that oppose norms or live in delicate political settings, are usually shoved aside. However, the writing, the reclaiming, is a resistance.

The story retrieves Hijab into the weaving of modern India’s formation by comparing letters, oral histories, and archival fragments.

The book is full of recollection and recovery, the fusion of the individual voice with the historical narrative results in an informative and personal style.

The readers become participants in the search; they share the author’s discovery, the outrage at erasure, and the pleasure of uncovering concealed clues. It is not a separate historical narrative but an animated experience of the past.

The emotional appeal is enhanced with instances of poetry. Her character is further enriched by the verse Hijab herself composes, in which she says, on the occasion of the doomsday, that she would confess her love to an unbeliever. Those lines remind us that she was not just a theme in Daggh’s poems; she was a poet, with words that were defiant and devotional.

That is the book’s strength: it is very thorough. It is based on Bengali biographies, family treasures, the writings of Hijab herself, and records of institutions in Glasgow, where she is still revered as the first woman fellow of the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons.

The abundance of sources is indicative of the difficulty posed by writing the history of women in South Asia, where archival silence is a frequent experience and oral tradition is charged with the responsibility of preservation.

Nevertheless, it also shows that these silences can be addressed, that washed-away lives can be restored to the light.

After all, the novel is an ode to endurance. The life of Hijab, with its fame and obscurity, success and tragedy, is the story of many women whose contributions to humanity have been neglected.

In reasserting her narrative, the book does justice to her and demands a more diverse and varied interpretation of the past.

It is a book that is not forgotten after reading the last page. The mixture of the past and the present, the richness of the details, the depth of emotions make it not merely a biography or a novel, but rather a reflection on memory, on love, and on women’s ability to mark themselves in history.

In putting Hijab back into focus, it is possible to say that she is no longer a shadow but a presence and a voice that transcends centuries. It reminds us that history is not fixed but is always rewritten, and even remembering itself is a form of justice.DD

Contributor, Diplomat Digital